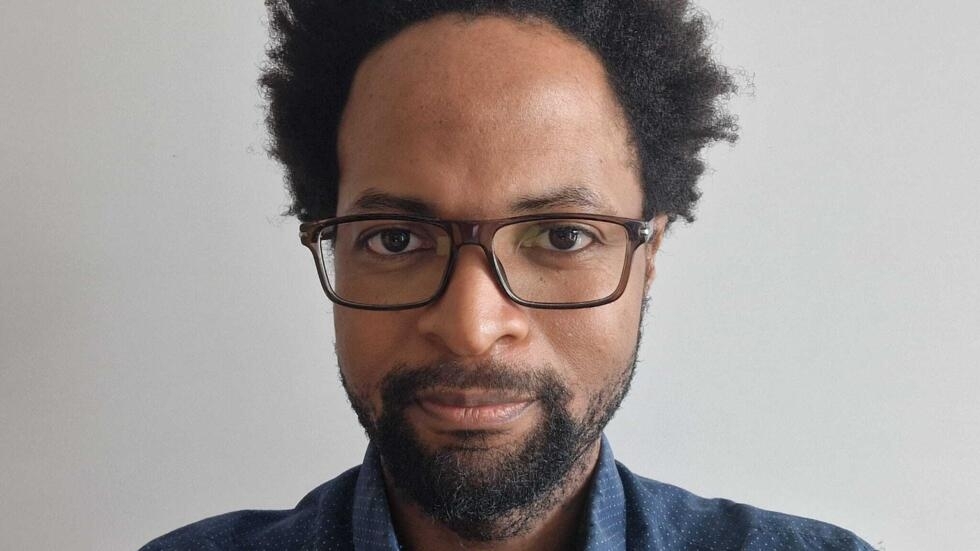

A member of the citizen movement Stand up for Cameroon, Remi Tassing, an engineer, devotes part of his free time to studying the allocation of public contracts in Cameroon. A solitary job that he readily describes as “thankless and austere”, based on documents posted online by Cameroonian institutions. Faced with the “anomalies” identified and denounced on the social network X, he dreams of a collective awareness. On June 1, 2024, he published a list of 203 agents, contract workers and civil servants, beneficiaries of public contracts in his country. Interview.

RFI: Remi Tassing, how did you become interested in public contracts?

Remi Tassing: As part of the citizen movement Stand Up for Cameroon, we work on issues of governance and corruption. For my part, I developed the Katika platform in 2018 on which I, for example, recorded incidents in the English-speaking regions.

As part of the “Covid Gate”, when the International Monetary Fund (IMF) demanded that Cameroon publish the list of budget beneficiaries, I began to take an interest in public procurement. It’s not my job. So I learned the Public Procurement Code, the Code of Transparency and Good Governance in the Management of Public Finances, an important document, but unfortunately not respected.

Cameroon has the difficulties of a poor country. But when we look at the budgets, the amounts, we wonder “where is the money going?”. With public procurement, there is a little traceability, insufficient certainly, but part of the iceberg is visible.

How do you work?

On this subject, I work alone, very early in the morning, around 4 or 5 a.m., or in the evening and on weekends, outside my working hours. I work only from accessible documents, posted online on the website of the Public Procurement Regulatory Agency (ARMP): calls for tender, awards, press releases. I cross-reference the information with data from the Cameroonian tax services. I identify anomalies, cases of overcharging, conflicts of interest and I publish on X, indicating as precisely as possible the names, contact details, identifiers.

This is not a journalist’s job, it is a whistleblower’s job. I provide journalists, NGOs, institutions with information, as detailed as possible, which I also indicate on the katika platform, more readable than the ARMP website.

What type of “anomalies” in the context of public procurement do you encounter?

I could talk about it all day. There are so many. One of the most recurring patterns is the purchase of vehicles at exorbitant prices. For example, a university rector launches a call for tenders in an “emergency” procedure for a vehicle at 100 million CFA francs [about 150,000 euros, Editor’s note]. In a country where some schools have no classrooms, some have no toilets, this is indecent.

Another example: public contracts awarded to unknown companies, which do not declare their income to the administration and do not pay taxes, or contracts awarded by local elected officials to companies… that belong to them. Once, I found a company benefiting from public contracts whose contact details were those of the CPDM[Cameroon People Democratic Movement, the majority party in Cameroon, Editor’s note]. This kind of case should cause a general outcry!

Who is taking over your alert work in Cameroon?

That’s what is painful. It’s like a black hole. Institutions such as ministries, the Chamber of Accounts, the Consupe (Higher State Control), the Conac (National Anti-Corruption Commission) and, of course, the justice system, particularly the TCS (Special Criminal Court) should take charge of these cases. But almost nothing is happening.

Journalists could take over more. But in Cameroon, they work in a repressive context. Result: this does not provoke the expected reactions.

In our country, public procurement is used to redistribute perks to members of the ruling party, the CPDM, through overcharging and kickbacks. This has been going on for years, but it has become disproportionate, out of control.

I do this alert work for my followers on my own scale. But I have neither the time nor the energy to do this on a larger scale.

Do you enter the institutions yourself?

No, I tag [digitally identify someone or something on the Internet, Editor’s note] the ministries and institutions concerned on X. I make the data available and I answer journalists’ questions when they ask me. Recently, I released a list of 200 public agents and civil servants identified in public markets. A census work over the last three years. And I continue to find some…

In principle, in Cameroon, all public markets of more than 5 million CFA francs must be declared to the Public Markets Regulatory Agency (ARMP), except in very specific, minority cases. But, over time, I have noticed that certain institutions never appear on the ARMP website: the Presidency of the Republic, the services attached to the Presidency, the services of the Prime Minister’s Office, the Senate, the National Assembly. However, these institutions should set an example. Not all their purchases are “defense secret”, it seems to me.

Do you receive financial support for this work?

No, no organization supports me. And when private individuals propose contributions, I refer them to the Stand up for Cameroon movement.

RFI